At the end of the excellent and under-watched 1982 documentary The Compleat Beatles, producer George Martin opines that the band’s success—in the extra-musical sense, which is to say, their cultural impact—owed much to their timing. A fascinating qualification follows, in which Martin notes that the Beatles themselves didn’t have any say in that timing themselves, but rather that it was chosen for them.

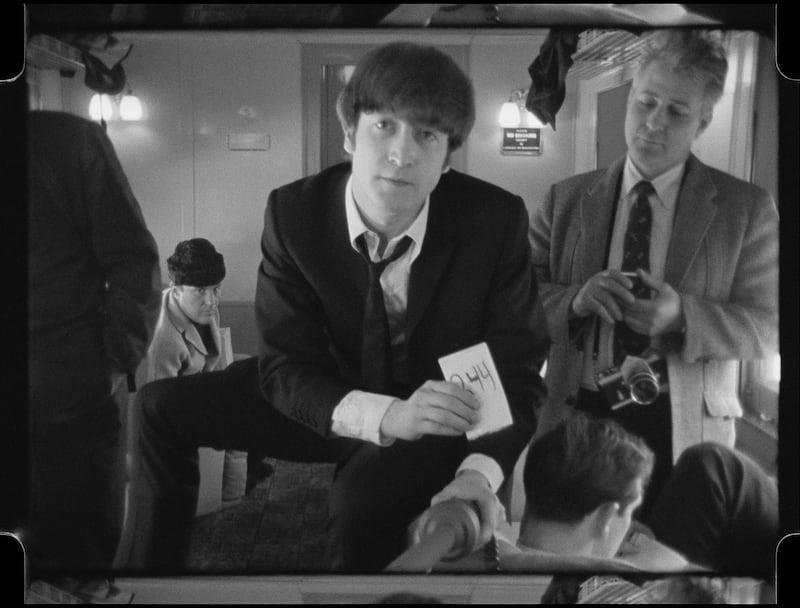

Director David Tedeschi’s 1964, streaming on Disney+ starting Thanksgiving Day, is a scrapbook-style documentary of the band’s first U.S. visit that John Lennon likened to a stint in the eye of a hurricane. The film is a curio, but an illuminating one. The timing angle is emphasized, with an extended opening sequence of archival footage and sound from John F. Kennedy’s presidency.

We see all manner of people reduced to tears with his assassination in late 1963, which is when the Beatles were releasing their second album in England, unbeknownst to the country that would soon take to them as no country had ever taken to any entertainers.

The lazy conclusion is one that has clotted rock history books for years: America was sad, the Beatles made them happy again.

There was more happening here, a unique confluence of historical, musical, and cultural factors waiting for someone to come along and be what Lennon, towards the end of the film in an old interview clip, rightly calls a figurehead. It was as if the Beatles were up in the crow’s nest of a ship, he says, these symbols who cried out, “Land, ho!”

Tedeschi relies heavily on footage shot by Albert and David Maysles for their own documentary (which is closer to a keeper and not a curio) on this flash-flood of a cultural event. The Beatles don’t happen as the Beatles without their initial reception in New York. And it was New York that was the key; if it’d been anywhere else, things would have been different.

What we learn in the film, if you weren’t already aware, is how little time America had to ramp up to adoration with the Beatles. To some—and I’d number among them—that made for what’s akin to a false-positive. The music of the Beatles was radical, arguably even more radical closer to the start than the finish, but that doesn’t mean it was commensurate with the adulation that awaited them when they landed in America.

We see people—often teenaged girls—who hadn’t a clue who the Beatles were a fortnight before the cameras began to roll in NYC and yet religious zealots presented with the Messiah in the flesh-and-blood could scarcely have been more super-charged with belief.

The archival interviews from the Beatles themselves, and those who knew their fair share of stuff, are especially valuable. We’ve talked about Lennon’s posthumous contributions, but we also have Little Richard, essentially saying he was too weird for these same American girls. Or, if not those girls themselves, their parents.

Little Richard and the Everly Brothers aside, the first wave of rock and roll was long on machismo. If Gene Vincent showed up to take out your kid—probably reeking of booze and with a switchblade somewhere on his person—you’d think that here was a problem. Elvis—with his pumping hips—wouldn’t have been much better. Little Richard presented a more feminized option, but to a white bread America, that would have been scarier.

Orson Welles remarked that the best artists are feminine. He didn’t mean outrightly female—but they had a feminine component. They traded in softness, vulnerability.

In the doc, Smokey Robinson touches on this idea, as does Jane Bernstein, Leonard’s daughter, who watched the band on The Ed Sullivan Show with her family. That first wave of rollers had come and gone. Teen idols followed, and you couldn’t care that much about a teen idol, whereas a whole lotta lust could be projected on a quartet of softer-seeming foreigners.

The Beatles weren’t here to stay—not geographically. They were the summer romance that played out during a few days in the winter of 1964.

Footage of the Beatles’ first U.S. concert in Washington, D.C. is an apt reminder for anyone who needs it—or a potent suggestion—that here would be one of the all-time great live albums if the show were officially released. Paul McCartney adds this giddy “Yeah” between some of the words of “From Me to You,” and it’s as rhapsodic a rock and roll moment as his, “Oh yeah/All right/Are you gonna be in my dreams/Tonight” farewell to Beatles-based rock and roll glory near the close of Abbey Road.

It’s worth noting that this was Beatlemania. Right here. The Beatles had staying power, but there was never anything like this first visit. Remember: Their arc was protracted temporally. Seven years as recording artists. There are two highs of highs; co-summits, if you like, to the phenomenon that was the Beatles. February 1964, and the release of Sgt. Pepper in June 1967. The former rocked the culture; the latter cracked the zeitgeist. A lot fell back to earth quickly in that second instance, with the death of manager Brian Epstein, and the missteps to follow, but the earlier event went faster still.

Fans who were there weigh in, as well as people like Ronnie Spector of the Ronettes and Ronald Isley of the Isley Brothers, who couldn’t understand the screaming for the life of him.

The Beatles were a four-person substrate on which young women projected what they wanted to project, or felt psychologically compelled to project. They were also a form of safe sex—the projection version of dry-humping from afar, or beneath the poster hanging over one’s bed.

The hotel room footage of the Beatles themselves is like a chilled out variant on their BBC radio sessions from the year before. The guys in their den, their clubhouse. Cracking wise, enjoying each other’s company.

A most amusing sequence involves a sardonic, clever wastrel—some random dude on the street—who tells a gaggle of girls he’s the Beatles’ manager, and then proceeds to put them down, while, paradoxically, discussing those aforementioned sexual and psychological factors with keen insight. One of the girls finally says, “You’re not really their manager, are you?” to which the guy says, no, he’s their brother.

It’s also ironic the sense of community fostered by this template the Beatles offered. The kids felt like they were in on something together. Well, some of them. A young man in Harlem says that Beatles aren’t anything compared to the bands led by John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and there are those out there who will say, “Obviously.”

But the Beatles as the Beatles aren’t the point. The phenomenon is, and that’s a different kettle of fish. Sometimes that kettle puts us at less-than-ideal remove from the music as music.

When “Please Please Me” burst forth from a transistor radio in the documentary, a new form of bell tolls. Listen to those ringing, clarion chords—lost on the screaming hordes, conceivably, but they are gone and the music remains.

We sense that someone had to be the Beatles, and these guys were them and were there. And if they hadn’t been, the job would have fallen to whomever it fell to. America was ripe, and, to their credit, the Beatles were ready.

Someone asks 1964 Paul McCartney about his band’s role in the shaping of Western culture, and he bursts out laughing at the notion. This isn’t culture, he says. It’s having a laugh.

But a well-timed laugh can also go a long way, and you know what they say about timing, even if it’s not quite everything.